People living with disabilities

Often invisible, overlooked and forgotten, people with disabilities are among the most socially excluded, isolated and marginalized of all displaced populations.

People with disabilities include “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” (UN, 2006).

People with disabilities face several categories of barriers:

-

Attitudinal

Behaviours, perceptions, and assumptions that discriminate against persons with disabilities

-

Organizational or systemic

Policies, procedures, or practices that unfairly discriminate and can prevent individuals from participating fully in a situation

-

Architectural or physical

Elements of buildings or outdoor spaces that create barriers to persons with disabilities (e.g., the design of a building's stairs or doorways, or the width of halls and sidewalks)

-

Information or communications

When sensory disabilities, such as hearing, seeing or learning disabilities, have not been considered

-

Technological

When a device or technological platform is not accessible to its intended audience and cannot be used with an assistive device

(Council of Ontario Universities, 2013) (Reid, 2020)

In addition to these barriers, refugees living with disabilities are often worse off because their traditional support systems (i.e., extended family, neighbours and other caregivers) disintegrate during displacement. The loss of these caregivers, due to separation during the displacement journey, puts persons with disabilities at high risk of abuse and neglect. All too often, they experience stigma and discrimination and have limited or no access to health care and psychosocial support, leading to greater levels of isolation than other refugees' experience. Immigrant individuals with disabilities or families with children who have a disability also deal with a loss of social ties as result of migration to another country (Khanlou et al., 2015, 2017).

While immigrants may generally have a greater support system than refugees, in some communities people attempt to hide their disabilities so they do not have a feeling of “otherness” or experience abuse or discrimination (Hansen et al., 2017). Support within the home is also sometimes not present as some immigrant parents of children with disabilities report a lack of support from their partners who withdraw from responsibilities as they deal with their own financial or emotional concerns (Khanlou et al., 2017).

Some disabilities in refugees are pre-existing, where the refugee had the disability prior to the conflict that led to migration. Other disabilities are directly caused or exacerbated by the refugee experience, often due to:

-

injury or trauma before or during the migration

-

lack of access to quality medical services

-

new barriers in the environment

Amendments to the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Protection Act in 2018 resulted in the increase of threshold cost amount (to three times the average Canadian per capita cost) for pre-existing medical conditions placing excessive demand on Canada's health and social services (Government of Canada, 2018). The grounds for inadmissibility do not apply to people being sponsored by their family, refugees and their dependents, or protected persons (Government of Canada, 2018). These temporary changes were made permanent in 2022 (Government of Canada, 2022).

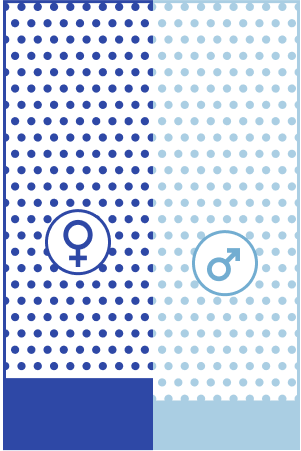

In 2017, the percentage of immigrant women aged 15 or older were more likely than immigrant men to report disabilities

(15.9% vs. 11.5%, respectively).

In addition, 21.4% of recent immigrants in 2017 were persons with a disability (Statistics Canada, 2018).

The percentage of immigrant men aged 15 and older in Canada, living with a disability was lower (17.7%) than that of non-immigrant men of the same age group living with a disability (21.4%).

Among recent immigrants, only 6.8% of men were persons with a disability in 2017 (Statistics Canada, 2018).

These extremely vulnerable refugees and immigrants need special attention as pressures around migration, acculturation and social relations may be more likely to affect their lives.